|

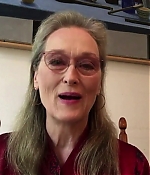

Simply Streep is your premiere online resource on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her acclaim to be one of the world's greatest living actresses. Created in 1999, Simply Streep has built an extensive collection over the past 25 years to discover Miss Streep's body of work through thousands of photographs, articles and video clips. Enjoy your stay and check back soon.

|

“The Prom” is coming to Netflix next week, and the first review are in, as compiled by Broadway World. The feel good Broadway musical, adapted for the screen, will arrive on December 11th. Find out what the critics had to say about the Ryan Murphy-helmed film, starring Meryl Streep, James Corden, Nicole Kidman, Keegan-Michael Key, Kerry Washington, Ariana DeBose, Andrew Rannells, and Jo Ellen Pellman, below. Many thanks to Glenn for the heads-up.

David Rooney, The Hollywood Reporter: “Whenever [Streep is] center-screen, this Netflix adaptation of the disarming 2018 Broadway musical sparkles with campy humor. Elsewhere, the starry casting and heavy hand of director Ryan Murphy do the featherweight material few favors, with inert dramatic scenes and overblown musical numbers contributing to the general bloat. The movie’s most undeniable value is in the representation it provides to LGBTQ teens via a high school dance that is every emotionally isolated queer kid’s rainbow dream.”

Mary Sollosi, Entertainment Weekly: “The Prom is narratively sloppy, emotionally false, visually ugly, morally superior, and at least 15 minutes too long (a strong case can be made for 30). It has good intentions, though; or at least it wants to have good intentions. Obviously – and positively! – the film preaches tolerance and inclusion, both of which the world needs more of.”

Owen Gleiberman, Variety: “There’s no denying that “The Prom,” like “Glee” and the “High School Musical” films, is on some level a knowingly assembled package of shiny happy film-musical clichés. Yet Murphy, working with the cinematographer Matthew Libatíque, gives the movie an intoxicating visual sweep, and there’s a beguiling wit to the dialogue.”

Richard Lawson, Vanity Fair: “There’s little good elsewhere in The Prom, save for newcomers Jo Ellen Pellman and Ariana DeBose as the winsome young couple at the center of the prom-troversy. They add dashes of bright theater-kid moxie to the film, conjuring up a bit of what it feels like to sit in a Broadway house and watch a bunch of lovable goobers belt their hearts out.”

Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian: “The Prom is an outrageous work of steroidal show tune madness, directed by the dark master himself, Ryan “Glee” Murphy, who is to jazz-hands musical theatre what Nancy Meyers is to upscale romcom or Friedrich Nietzsche to classical philology.”

Ben Travis, Empire: “In recent years, there’s been a spate of musicals that you’ll enjoy ‘even if you don’t like musicals’, like Hamilton with its astonishing word-wizardry, or the retro-cool La La Land. The Prom is no such musical. It is intensely, unabashedly, razzlingly, dazzlingly Broadway, a musical for people who love musicals, in which many of the songs are about musicals. Anyone allergic to such things need not apply.”

Tim Robey, The Telegraph: “The whole thing drips with garish insincerity and preaching to the choir. Irony of ironies, that a show about out-of-touch luvvies swanning down to wave their magic wands at red-state intolerance has become… the spitting image of that, as a home cinema offering from Murphy and team.”

Lewis Knight, Mirror: “With glitz and glamour, Ryan Murphy offers a fun and lightweight musical that will certainly not win over the sort of people who detest the genre but will likely entertain those who do.”

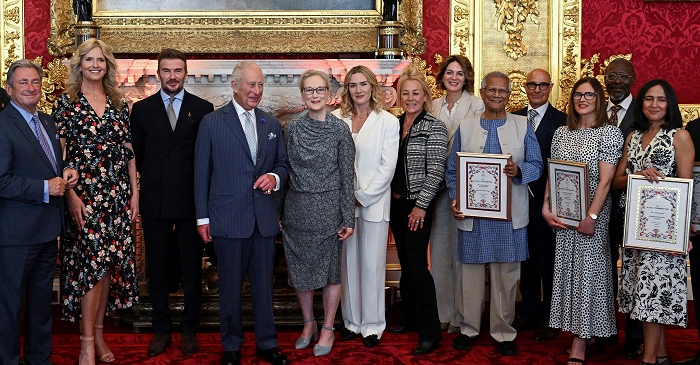

Three remarkable actress – Academy Award-winners Meryl Streep and Dianne Wiest, and Emmy Award-winner Candice Bergen – share the screen in a new film by director Steven Soderbergh, “Let Them All Talk,” an exercise in improvisation, in which its actors were required to create much of the dialogue themselves. Correspondent Rita Braver talks with the trio about the rarity of starring in a major Hollywood film about three women in their 70s.

Video Archive – News Segments – CBS Sunday Morning (November 29, 2020)

Photo Gallery – Television Appearances – CBS Sunday Morning (November 29, 2020)

“I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills”. This is how Karen Blixen starts “Out of Africa”, her probably most famous novel, first published in 1937. It’s her account on living in – and falling for – Africa for 17 years, written under her well-known pen name Isak Dinesen. The trademark line also opened Sydney Pollack’s 1985 Oscar-winning film of the same name, which introduced Karen Blixen’s life and love story to a new generation of moviegoers and readers.

Isak Dinesen was the pseudonym used by the Danish author Karen Dinesen Blixen-Finecke (1885-1962). Her stories place her among Denmark’s greatest authors. Isak Dinesen was born on April 17, 1885, the daughter of a wealthy landowner, adventurer, and author. In 1914 she went to Africa, married, and bought a coffee plantation. After her divorce in 1921 she managed the plantation alone until economic disaster forced her to return to Denmark in 1931, where she lived the rest of her life on the family estate, Rungstedlund, near Copenhagen. The years in Africa were the happiest of Dinesen’s life, for she felt, from the first, that she belonged there. Had she not been forced to leave, she wrote later, she would not have become an author. In the dark days just before leaving, she began to write down some of the stories she had told to her friends among the colonists and natives. She wrote in English, the language she used in Africa. Her books usually appeared simultaneously in America, England, and Denmark, written in English and then rewritten in Danish.

Dinesen’s first collection, Seven Gothic Tales, appeared in America in 1934, where it was a literary sensation, immediately popular with both critics and public. The Danish critical reaction was cool. Danish literature was still dominated by naturalism, as it had been for the past 60 years, and her work was a reaction against this sober, realistic fiction of analysis. Dinesen’s second book, Out of Africa (1937), a brilliant recreation of her African years, was a critical and popular success wherever it appeared. Although it has little in common, stylistically and formally, with her stories, it describes the experiences which formed her views about life and art. The third central work in her authorship, Winter’s Tales, appeared in 1942. A characteristic of Dinesen’s works is the sense that the reader is listening to a storyteller. She wanted to revive in her “listeners” the primitive love of mystery that she found in her African audience, which she felt was like the audiences that listened to Homer, the Old Testament stories, the Arabian Nights, and the sagas. She attempted to reawaken the sense of myth and, with myth, the sense of man’s tragic grandeur, which she felt had been lost.

Fifteen years after Winter’s Tales, Dinesen published Last Tales (1957), containing some of her finest stories. This volume includes “The Cardinal’s First Tale,” an excellent defense of her art and a critique of naturalism. In 1958 appeared Anecdotes of Destiny. Her last book, Shadows on the Grass (1961), is a pendant to Out of Africa. Dinesen was the first Danish author to achieve world fame since Hans Christian Andersen and Søren Kierkegaard. Her influence on Danish literature was especially strong in the 1950s when, through her stories and personal contact, she was an inspiration to younger authors searching for new means of expression. She died on September 6, 1962.

Sydney Pollack based his epic 1985 film “Out of Africa” on Karen Blixen, from Judith Thurman’s book “Isak Dinesen: The Life of a Story Teller”. While Meryl Streep didn’t speak much about the real-life Karen Blixen while promoting the film, she gave some insight into the script in an interview with Wendy Wasserstein in 1988: “I thought it was a great script, but there was this one line that I thought was just preposterous, and I didn’t know how I was going to get it out. I didn’t want to say it. I didn’t mind being proprietary about “my” Africans, or Karen Blixen’s other sort of grande-dame pretensions; but when Dennis suggests taking their young friend along on one of his flights and she rises up from her chair and syas, “I won’t allow it, Dennis,” I though it sounded like a mother admonishing her child, which did not reflect their relationship at all. It felt like a little vehicle, like a car that he could get into and slam the door and peel out in. Without that line, did he have enough reason to storm out of her life in a big huff? I though this was a really good argument. When we came to do the scene, I said, “All right, you know, I’m a good sport, I’ll say it, and I’ll try to make it work, but it won’t.” And, of course, when we played it, it was the easiest and freest thing she said in the scene, because all the reason had been used up; there was nothing left to argue with but her desperation, and it was so preposterous and pathetic that it was right. It was a key to the woman. I hate it when they’re right.”

Isak Dinesen: Life of a Storyteller by Judith Thurman (1995)

Out of Africa by Karen Blixen (1937)

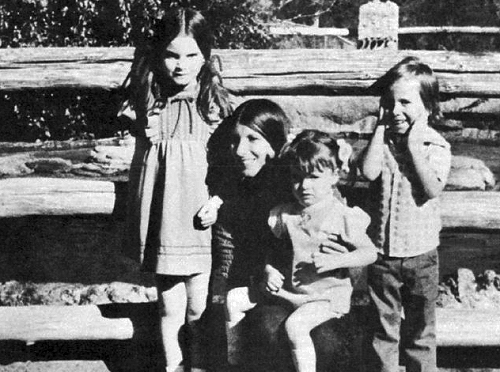

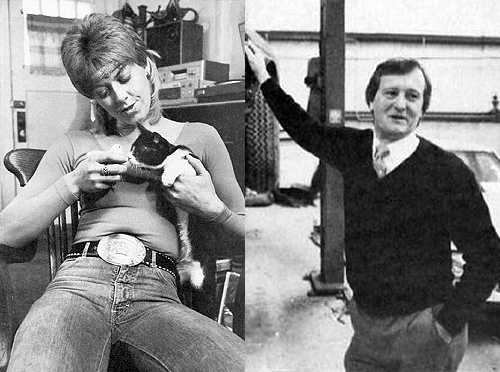

Was Karen Silkwood, a nuclear plant employee at Kerr McGee, just a trouble maker? Or did she really had sensitive information collected that would prove a contaminating of plutonium, based on security holes that her bosses knew of? Through her untimely death in 1974, which will most probably remain mysterios forever, there are no answers to this question. Her story was made into a film in 1983 in which, for the first time, Meryl portrayed a person that has really lived.

On the night of November 13, 1974, Karen Silkwood, a technician at the Kerr-McGee Cimarron River nuclear facility in Crescent, Oklahoma, was driving her white Honda to Oklahoma City. There she was to deliver a manila folder full of alleged health and safety violations at the plant to a friend, Drew Stephens, a New York Times reporter and national union representative. Seven miles out of Crescent, however, her car went off the road, skidded for a hundred yards, hit a guardrail, and plunged off the embankment. Silkwood was killed in the crash, and the manila folder was not found at the scene when Stephens arrived a few hours later. Nor has it come to light since. Although Kerr-McGee was a prominent Oklahoma employer whose integrity had never been challenged, as a part of the nuclear power industry it had many adversaries.

Silkwood was born in Texas, went through one year of college and had three children by a common-law husband, whom she left when she moved to Crescent, Okla., to work in Kerr-McGee’s Cimarron Plutonium Recycling Facility there. At Cimarron, she earned a reputation as someone who couldn’t be pushed around. She lived for a while with a young co-worker named Drew Stephens and was known to drink and to pop pills. At the same time, she grew increasingly troubled by the sloppy safety conditions under which she and the other Cimarron employees worked when handling dangerous, highly radioactive plutonium. One result was that she threw herself into union work and was herself “contaminated” by radioactive materials, though in ways that have never been satisfactorily explained. At the time of her death, she was alleged to have gathered evidence that would force the plant to close.

On the night of the car crash, she was driving alone to Oklahoma City to meet David Burnham, a reporter for The New York Times, to tell her story. Because of these circumstances, there are those who contend that she was murdered to keep her silent. At this point she had become almost as unpopular with many employees, who didn’t want to lose their jobs, as she was with management. There are others who are certain further that her contaminations were, in fact, not accidents but self-inflicted, in an attempt to dramatize the true gravity of conditions at the Cimarron facility, which, subsequently, was shut down. The controversy ignited by Silkwood’s death regarding the regulation of the nuclear industry was intense, with critics finally finding an example around which to focus their argument. The legacy of the Silkwood case continues to this day in the on-going debate over the safety of nuclear technology. Since then, her story has achieved worldwide fame as the subject of many books, magazine and newspaper articles, and even a major motion picture. Silkwood was a chemical technician at the Kerr-McGee’s plutonium fuels production plant in Crescent, Oklahoma, and a member of the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers’ Union. She was also an activist who was critical of plant safety.

During the week prior to her death, Silkwood was reportedly gathering evidence for the Union to support her claim that Kerr-McGee was negligent in maintaining plant safety, and at the same time, was involved in a number of unexplained exposures to plutonium. The circumstances of her death have been the subject of great speculation. Speculation about foul play in Silkwood’s death has never been substantiated. However, some independent investigators at the time inferred that her vehicle had been hit from behind and forced off the road. Public suspicions led to a federal discussion into plant investigation security and safety, and a National Public Radio report about 44 to 66 pounds of misplaced plutonium. Silkwood’s story emphasized the hazards of nuclear energy and raised questions about corporate accountability and responsibility. According to the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union, the Kerr-McGee plant had manufactured faulty fuel rods, falsified product inspection records, and risked employee safety. Eventually, Kerr-McGee closed the plant. In 1986, Silkwood’s family, represented by Gerry Spence, settled an $11.5 million plutonium-contamination lawsuit against Kerr-McGee for $1.38 million.

In an interview to promote the theatrical release of “Silkwood”, Meryl Streep said: “I was attracted to the character. No matter what I think in my real life, in order to effectively play a part or make my imagination go, I have to be presented with a certain challenge and a character with problems. What I liked about Karen was that she wasn’t Joan of Arc at all. She was unsavory in some ways and yet she did some very good things. This doesn’t feel like an antinuclear movie. There are lots of those around, and I’ve stayed away from them quite purposefully because I don’t like polemics. This film is more complicated, it seems to be, and evenhanded in a funny, real-life way. The people on both sides of the question are all pretty recognizable. It has the feeling of real working life, and I think it’s about that more than anything nuclear. It was interesting to me that some of the people who were playing party in this movie, mainly Kurt, met the people they were playing. I was meeting no one; all I had were pieces of information from different pieces of information from different sources. I had details from five or six people that all described a different woman. It made me think I really ought to write my autobiography before I go, because once you’re gone, everybody has a different version of you”.

The Killing of Karen

Silkwood: The Story Behind the Kerr-McGee Plutonium Case by Richard Rashke (1981)