|

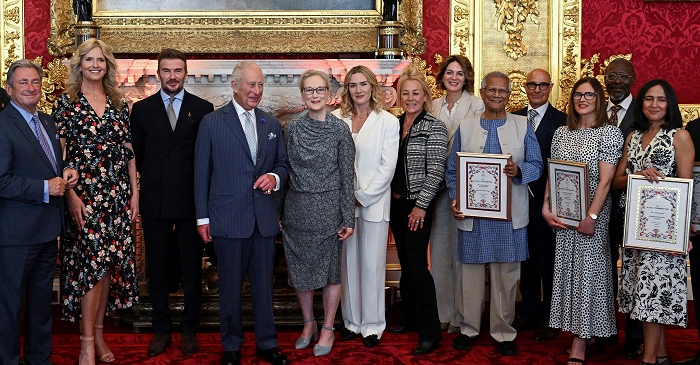

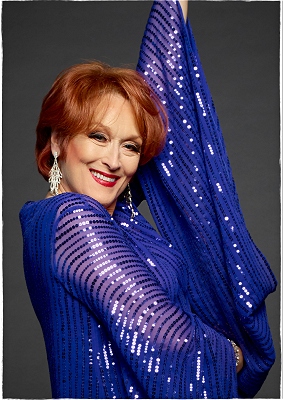

Simply Streep is your premiere online resource on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her acclaim to be one of the world's greatest living actresses. Created in 1999, Simply Streep has built an extensive collection over the past 25 years to discover Miss Streep's body of work through thousands of photographs, articles and video clips. Enjoy your stay and check back soon.

|

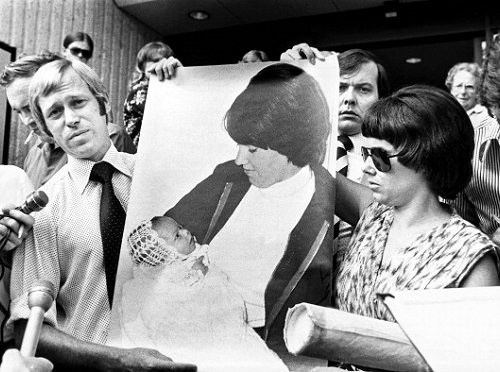

In 1980, Lindy Chamberlain’s case and the story of her infant daughter’s disappearance shocked Australia. Through disbelief that a wild dog could be responsible, Lindy was sentenced to life for murdering her child and pardoned years later after new evidence was found. One the worst cases of crime injustice in the history of Australia, Lindy’s story was made into a documentary-style film, and starring Meryl Streep in a performance as the woman who still divides a continent.

Michael and Lindy Chamberlain’s first daughter, Azaria, was born on June 11, 1980. When Azaria was two months old, Michael and Lindy Chamberlain took their three children on a camping trip to Uluru, arriving on August 16, 1980. On the night of August 17, Chamberlain reported that the child had been taken from her tent by a dingo. A massive search was organised, but all that was found were remains of some of the bloody clothes, which confirmed the death of baby Azaria. Her body has never been discovered, and it is thought that the baby’s body was consumed by the dingos. Although the initial coronial inquiry supported the Chamberlains’ account of Azaria’s disappearance, Lindy Chamberlain was later prosecuted for the murder of her child on the basis of the finding of the baby’s jumpsuit and of tests that appeared to indicate the presence of blood found in the Chamberlains’ car. She was convicted of murder on October 29, 1982, and sentenced to life imprisonment; the theory was that she slit the child’s throat and hid the body. Michael Chamberlain was convicted as an accessory to murder. Shortly after her conviction, Lindy Chamberlain gave birth to her fourth child, Kahlia, on November 17, 1982, in prison. An appeal against her conviction was rejected by the High Court in February, 1984.

New evidence emerged on February 2, 1986 when a remaining item of Azaria’s clothing was found partially buried near Uluru in an isolated location, adjacent to a dingo lair. This was the matinee jacket which the police had maintained for years did not exist. Five days later, Chamberlain was released. The Northern Territory Government publicly said it was because “she had suffered enough.” In view of inconsistencies in the earlier blood testing which gave rise to potential reasonable doubts about the propriety of her conviction and as DNA was not as advanced in the early 1980s it emerged that the ‘baby blood’ found in her car could have been any substance, Lindy Chamberlain’s life sentence was remitted by the Northern Territory Government and a Royal Commission began to investigate the matter in 1987. Chamberlain’s conviction was overturned in September, 1988 and another inquest in 1995 returned an open verdict. The cause of Azaria’s disappearance has not been officially determined. The last and final official inquest listed the cause of her death as “undetermined.” A body has never been found, only various items of bloodstained clothing. The Chamberlains, who were originally convicted, have been officially exonerated by the Court and eventually received some financial compensation. It is estimated that their legal fees exceeded five million Australian Dollars. In August 2005, a 25-year old woman named Erin Horsburgh claimed that she was Azaria Chamberlain, but her claims were rejected by the authorities and the ABC’s Media Watch program, who stated that none of the reports linking Horsburgh to the Chamberlain case had any substance. The Chamberlains divorced in 1991 and Lindy Chamberlain has since remarried.

In 2012, over 30 years after the disappearance, the case was finally solved. Northern Territory Coroner Elizabeth Morris found evidence from the case proved a dingo or dingoes were responsible for Azaria’s death and ruled that her death certificate should read “attacked and taken by a dingo”. In an emotional finding, Morris offered her condolences to the Chamberlains, who were in the Darwin court room. “Please accept my sincere sympathy on the death of your special loved daughter and sister Azaria. I am so sorry for your loss,” she said to the family. “Time does not remove the pain and sadness of the death of a child.”

When “A Cry in the Dark” was in pre-production, Lindy Chamberlain was still imprisoned, and there was no sign of her exoneration in 1987. So by the time of its filming, Meryl Streep not only portrayed another real-life character, but a convicted murderer. With the new-found evidence and Miss Chamberlain’s exoneration, the already heavily debated case became even more current. As Streep told Entertainment Weekly in 2000, “there were enormous legal considerations over every line I said, because Lindy Chamberlain was pressing the government to be exonerated. Along with all the other challenges of making a movie, to have lawyers sitting there… There was no doubt in my mind that she was innocent. And they did exonerate her. But because of her manner, she was condemned. She wasn’t the weeping, screaming, bereaved mother – she was more like ‘None’a your fucking business how I feel!’ There are people you just want to tell, ‘You know, you’ll get further in life if you just…’ She was vilified for the shape of her eyebrows, because they pointed down and she looked mad all the time.”

Through My Eyes by Lindy Chamberlain (1991)

Lindy Chamberlain: The Full Story by Ken Crispin (1989)

Evil Angels by John Bryson (1987)

Roberta Guaspari’s story had Hollywood written all over it: A mother of two young sons emerges from a failed marriage and finds her calling teaching violin at a New York City public school in East Harlem. When budget cuts threaten to close her program, she fights City Hall and wins. In 1999, eight years after Guaspari’s efforts were first chronicled by the media, Roberta’s story was brought to the screen in Wes Craven’s Oscar-nominated drama “Music of the Heart”.

Roberta Guaspari began studying violin in fourth grade. She eventually graduated with a music education degree from the State University of New York at Fredonia in 1969. While working on her master’s at Boston University, she met George Tzavaras, a Navy officer studying at MIT. “I was 24, Italian and not married,” she says. “The pressure was on from my family.” They wed in 1971. As George rose through Navy ranks – with postings in Honolulu and Newport, R.I. – the family was always on the move. Teaching violin and persuading school administrators to invest in musical instruments proved a dauntingly tough career choice, especially after the birth of the couple’s two sons. Finally, when the family moved to Greece in 1977, Roberta devised a solution. Withdrawing $5,000 from the family savings, she bought 50 tiny violins and persuaded the headmaster of the British-run Campion School to hire her. No sooner had Guaspari-Tzavaras established herself there than George asked for a divorce. “It was the lowest point of my life,” she says.

But Guaspari-Tzavaras rebounded. With her sons – and violins – in tow, she moved to New York City in 1980, subletting an East Harlem apartment from a couple whose children attended Central Park East schools, a city-run alternative program. That led to an introduction to the school’s music-loving principal, Deborah Meier, and a part-time job. Three years later, when she was hired full-time, Guaspari-Tzavaras had fallen in love again – this time with her gritty new neighborhood, where she lovingly restored the townhouse she lives in with Sophia, a 5-year-old from El Salvador, whom she adopted in 1991. “My mother really needs to come home and be a mother,” says Alexi. “She is just as passionate about mothering as she is about teaching.”

And there are those who are passionate about her. In 1993, world-class violinists, including Itzhak Perlman and Arnold Steinhardt, helped organize a Carnegie Hall benefit concert that raised nearly $300,000 for her program. “This woman has an incredible, demonic amount of energy,” says violin virtuoso Isaac Stern. “She draws things out of the kids. And from her they gain a sense of self.” That’s certainly true for Guaspari-Tzavaras alum Melia Crumbley, 15. When kids who hang out on the street mock her for spending so much time practicing, says Melia, “I just look them right back in the eye and say, ‘What are you doing with your life?” A documentary film about Roberta called Small Wonders was nominated for an Academy Award in 1996. Further developments inspired by this teacher include a feature film, released in October 1999. Music of the Heart starred Meryl Streep as real-life violin teacher Roberta Guaspari-Tzavaras.

Meryl Streep was a literally last-minute replacement for Wes Craven’s “Music of the Heart”, after Madonna dropped out of the project. Streep was given six weeks for preparation in order to play the violin. “I had to beg them to give me some more time for the violin part of it.” Streep, aside from having the daunting task of learning the violin while acting like a professional, also had the burden of playing a real person. She found this to be particularly challenging. “Playing a real person carries with it a whole other set of responsibilities than you would have when creating a fictional character,” Streep continues, “So, I did as much research as I could and then I just sort of threw it away because I can’t think of the real Roberta. I had to make it our Roberta, our movie Roberta. The real woman is a sizable phenomenon of energy, inspiration, hard work, irascibility. I tried to capture little parts of her and put it together in the film.”

“I came here to forgive, but all I can do is taking pleasure in your misery. Knowing that I would get to see you die, more terribly than I did”. In an Emmy-winning performance in “Angels in America”, Meryl Streep played the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, visiting – and haunting – lawyer Roy Cohn on his deathbed. What lies behind this tragic-coming episode of the award-winning mini-series is a tragic and still controversial episode of the 1950’s anti-communist hysteria.

Ethel Rosenberg was born September 28, 1915 in New York City. She attended a religious school and then Seward Park High School, where she graduated at the age of only 15. Ethel became a clerk for a shipping company immediately after finishing school. She remained at this job for the next four years until she was let go because of her role as the organizer of a strike of 150 women workers. Ethel was not just an activist at work, she was also interested in politics. Ethel joined the Young Communist League and eventually became a member of the American Communist Party. In addition to her clerk job, Ethel enjoyed singing, alone as well as with a choir. Ethel was waiting to go on stage to sing at a New Years Eve benefit when she first met Julius Rosenberg. The couple was married not long afterwards in the summer of 1939. Although mentally tough, Ethel Rosenberg’s body was weak. She was not healthy enough to work after the Rosenberg’s were married. Instead, Ethel stayed home with their two sons Michael and Robert. By the summer of 1950, Ethel’s younger brother, David Greenglass, had named Julius as a participant in the spy ring. The FBI questioned her husband and eventually placed him under arrest. On August 11, 1950, Ethel Rosenberg was herself arrested.

Ethel Rosenberg and her husband, Julius were convicted of passing nuclear weapons secrets to the Soviet Union and were executed in 1953. Since then, decrypted Soviet cables have appeared to confirm that he was a spy, but doubts have remained about her role. At the Rosenbergs’ trial, the key testimony against Ethel Rosenberg came from her brother and sister-in-law, David and Ruth Greenglass. They testified that Ethel Rosenberg had typed stolen atomic secrets from notes provided by David Greenglass. The testimony provided the direct involvement that the jury needed to convict and that the judge needed to sentence Ethel to death. In recent years, David Greenglass recanted his testimony about the typing. Historians spotted a major omission in Ruth Greenglass’ pretrial grand jury testimony: She did not testify that she saw Ethel Rosenberg type up the secrets. In fact, Ruth Greenglass testified that she herself wrote out the secrets in longhand. Soviet cables described material received from the Rosenbergs as being in longhand. Ruth Greenglass’ pretrial testimony confirms that her husband’s trial claim was a fabrication, said Georgetown University law professor David Vladeck, who helped gain release of the transcripts.

Roy Cohn, as portrayed by Al Pacino in “Angels in America”, was an American conservative lawyer who became famous during the investigations by Senator Joseph McCarthy into alleged Communists in the U.S. government, and especially during the Army-McCarthy Hearings. He was also an important member of the prosecution team for the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Cohn’s direct examination of Ethel’s brother David Greenglass produced the testimony (in which the brother later claimed he perjured himself) that was mostly responsible for the Rosenbergs’ conviction and execution. Cohn took great pride in the Rosenberg case, and claimed to have played an even greater part than his public role: he said in his autobiography that his own influence had led to both Saypol and Judge Irving Kaufman (a family friend) being appointed to the case, and that Kaufman had imposed the death penalty on Cohn’s personal advice. A homosexual in the closet, Cohn was diagnosed with AIDS in 1984 and attempted to keep his condition secret while receiving aggressive drug treatment. He insisted to his dying day that his disease was liver cancer. A controversial man in life, Cohn inspired many dramatic fictional portrayals after his death. Probably the most famous is his role in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes, in which Cohn is portrayed as a self-hating, power-hungry hypocrite who is haunted by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg.

While not a biopic or an in-depth look at Rosenberg’s life, Meryl Streep played “the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg” in Mike Nichols’ acclaimed television adaptation of “Angels in America” in 2003. While speaking to Interview Magazine to promote its release, Streep said “I just thought her story was so horrific that there had to be something else. Plus she had God on her side, so there’s something to smile about there. But I don’t know where these things come from. She was just there at the first reading.”

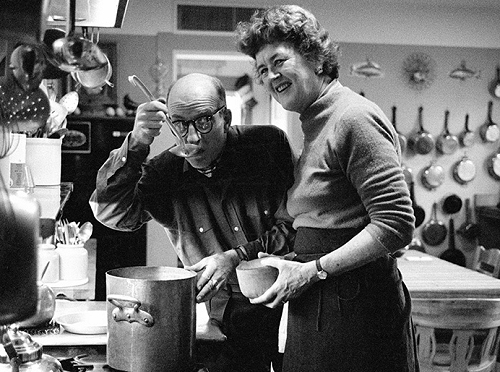

The making of the cultural phenomenon that was Julia Child had three key ingredients: a man, a meal, and a TV camera. Five years after Child’s death, as Meryl Streep plays the woman who revolutionized America’s relationship with food, cinema audiences learned more about the wartime romance between Julia and her husband Paul, the television appearance that turned her into “The French Chef” – and her book “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” into a kitchen bible.

Born Julia McWilliams, on August 15, 1912, in Pasadena, California. The eldest of three children, Julia was educated at San Francisco’s elite Katherine Branson School for Girls, where – at a towering height of 6 feet, 2 inches – she was the tallest student in her class. Upon her graduation from Smith College in 1930, she moved to New York, where she worked in the advertising department of the prestigious home furnishings company W&J Sloane. In 1941, at the onset of World War II, Julia moved to Washington, D.C., where she volunteered as a research assistant for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a newly formed government intelligence agency. She and her colleagues were sent on assignment to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), an island off the coast of India. In her position, Julia played a key role in the communication of top secret documents between U.S. government officials and their intelligence officers. In 1945, she was sent to China, where she began a relationship with fellow OSS employee Paul Child. Following the end of World War II, the couple returned to America and were married. In 1948, when Paul was reassigned to the U.S. Information Service at the American Embassy in Paris, the Childs moved to France. While there, Julia developed a penchant for French cuisine and attended the world-famous Cordon Bleu cooking school.

Following her six-month training – which included private lessons with master chef Max Bugnard – Julia banded with fellow Cordon Bleu students Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle to form the cooking school L’Ecole de Trois Gourmandes. With a goal of adapting sophisticated French cuisine for mainstream Americans, the trio collaborated on a two-volume cookbook titled Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961). Published in the U.S., the 800-page book was considered a groundbreaking work and has since become a standard guide for the culinary community. Then living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Julia promoted her book on the Boston public broadcasting station. Displaying her trademark forthright manner and hearty humor, she prepared an omelet on air. The public’s response was so enthusiastic that she was invited back to tape her own series on cookery for the network. Premiering on WGBH in 1962, The French Chef TV series, like Mastering the Art of French Cooking, succeeded in changing the way Americans related to food, while also establishing Julia as a local celebrity. Shortly thereafter, The French Chef was syndicated to 96 stations throughout America. For her efforts, Julia received the prestigious George Foster Peabody Award in 1964 followed by an Emmy Award in 1966.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Julia made regular appearances on the ABC morning show Good Morning, America. Her other endeavors included the television programs Julia Child and Company (1978), Julia Child and More Company (1980), and Dinner at Julia’s (1983), as well as a slew of bestselling cookbooks that covered every aspect of culinary knowledge. In 1993, Julia was the first woman inducted into the Culinary Institute Hall of Fame. Her most recent cookbooks were In Julia’s Kitchen with Master Chefs (1995), Julia’s Delicious Little Dinners (1998), and Julia’s Casual Dinners (1999), which were all accompanied by highly rated television specials. In November 2000, following a 40-year career that has made her name synonymous with fine food, Julia received France’s highest honor: the Legion d’Honneur. And in August 2002, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History unveiled an exhibit featuring the kitchen where she filmed three of her popular cooking shows. Child died in August 2004 of kidney failure at her assisted-living home in Montecito, two days before her 92nd birthday. After her death Child’s last book, the autobiographyMy Life in France, was published with the help of Child’s great nephew, Alex Prud’homme. The book, which centered on how Child discovered her true calling, became a best seller.

Meryl Streep talked about Julia Child in length while promoting “Julie & Julia” in 2009. “When you talk about passion, Julia Child just didn’t have it for her husband or cooking; she had a passion for living. What was compelling about her was her joie de vivre and her unwillingness to be bogged down in negativity. She loved being alive and that’s inspirational in itself. I saw her cooking shows when I was a kid. She was a pioneer because she was one of the first women on television who wasn’t an entertainer and she was already 50 years old, with her personality indelibly created by her own life experience. There was no focus group telling her how to dress and look, and her generous nature was what drew people to her. Julia’s personality was so much like my mother’s that I felt very familiar with it. My mother had an undeniable sense of how to enjoy her life, and she made every room she walked into brighter. She really was something, and all my life I wanted to be more like my mother. So this is my little tribute to that spirit. Unfortunately, in my own life I can be a real whiner. The cookbook my mother used was Peg Bracken’s I Hate To Cook. I remember when I was 10 going over to a friend’s house and she and her mom were seated at the kitchen table and they were doing something with what looked liked tennis balls, these big white things. They said, ‘We’re making mashed potatoes.’ I went, ‘What do you mean? Mashed potatoes come in a box.’ I’d never seen a peeled potato. My mother’s motto was, ‘If it’s not done in 20 minutes, it’s not dinner.’ She had a lot of things that she wanted to do and cooking was not one of them.”

Here’s a list of Julia Child’s many books. A link on the title will forward you to Amazon. Most of the books are still available and can be ordered.

Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961) with Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle

Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume Two (1970) with Simone Beck

The French Chef Cookbook (1968)

From Julia Child’s Kitchen (1975)

Julia Child & Company (1978)

Julia Child & More Company (1979)

The Way To Cook (1989)

Julia Child’s Menu Cookbook (1991), one-volume edition

Cooking With Master Chefs (1993)

In Julia’s Kitchen with Master Chefs (1995)

Baking with Julia (1996)

Julia’s Delicious Little Dinners (1998)

Julia’s Menus For Special Occasions (1998)

Julia’s Breakfasts, Lunches & Suppers (1999)

Julia’s Casual Dinners (1999)

Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home (1999)

Julia’s Kitchen Wisdom (2000)

My Life in France (2006, posthumous), with Alex Prud’Homme

From her first days in power, Margaret Thatcher developed and refined ways of circumventing political protocol and procedure. Serving three consecutive terms in office until 1991, Thatcher remains one of the dominant political figures of 20th century Britain- and one of the most controversal in history. Her life and career was portrayed in fragments and flashbacks by Meryl Streep in “The Iron Lady”.

Margaret Hilda Roberts was born on 13 October 1925 in Grantham, Lincolnshire, the daughter of a grocer. She went to Oxford University and then became a research chemist, retraining to become a barrister in 1954. In 1951, she married a wealthy businessman, Denis Thatcher, with whom she had two children. Thatcher became Conservative member of parliament for Finchley in north London in 1959, serving as its MP until 1992. Her first parliamentary post was junior minister for pensions in Harold Macmillan’s government. From 1964 to 1970, when Labour were in power, she served in a number of positions in Edward Heath’s shadow cabinet. Heath became prime minister in 1970 and Thatcher was appointed secretary for education. After the Conservatives were defeated in 1974, Thatcher challenged Heath for the leadership of the party and, to the surprise of many, won. On 19 January, 1976, Thatcher made a speech in Kensington Town Hall in which she made a scathing attack on the Soviet Union. “The Russians are bent on world dominance, and they are rapidly acquiring the means to become the most powerful imperial nation the world has seen.

The men in the Soviet Politburo do not have to worry about the ebb and flow of public opinion. They put guns before butter, while we put just about everything before guns.” In response, the Soviet Defence Ministry newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star) gave her the nickname “Iron Lady”. Thatcher took delight in the name, and it soon became associated with her image. Despite an economic recovery in the late 1970s, the Labour government faced public unease about the direction of the country and a damaging series of strikes during the winter of 1978–79, popularly dubbed the “Winter of Discontent”. The Conservatives attacked the Labour government’s unemployment record, using advertising with the slogan Labour Isn’t Working. A general election was called after James Callaghan’s government lost a motion of no confidence in early 1979. The Conservatives won a 44-seat majority in the House of Commons, and Margaret Thatcher became the UK’s first female Prime Minister.

If our people feel that they are part of a great nation and they are prepared to will the means to keep it great, a great nation we shall be, and shall remain. So, what can stop us from achieving this? What then stands in our way? The prospect of another winter of discontent? I suppose it might. But I prefer to believe that certain lessons have been learnt from experience, that we are coming, slowly, painfully, to an autumn of understanding. And I hope that it will be followed by a winter of common sense. If it is not, we shall not be—diverted from our course. To those waiting with bated breath for that favourite media catchphrase, the ‘U-turn’, I have only one thing to say: “You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning. (Margaret Thatcher, Conservative Party Conference, 10 October 1980)

An advocate of privatisation of state-owned industries and utilities, reform of the trade unions, the lowering of taxes and reduced social expenditure across the board, Thatcher’s policies succeeded in reducing inflation, but unemployment dramatically increased. In 1982, the ruling military junta in Argentina ordered the invasion of the British Falkland Islands and South Georgia, triggering the Falklands War. The subsequent crisis was “a defining moment of Thatcher’s premiership”. She set up and chaired a small War Cabinet (formally called ODSA, Overseas and Defence committee, South Atlantic) to take charge of the conduct of the war, which by 5–6 April had authorised and dispatched a naval task force to retake the islands. Argentina surrendered on 14 June and the operation was hailed a success, notwithstanding the deaths of 255 British servicemen and 3 Falkland Islanders. Thatcher was criticised for the neglect of the Falklands’ defence that led to the war, but overall she was considered a highly talented and committed war leader. The “Falklands factor”, an economic recovery beginning early in 1982, and a bitterly divided Labour opposition contributed to Thatcher’s second election victory in 1983. In 1984, she narrowly escaped death when the IRA planted a bomb at the Conservative party conference in Brighton. In foreign affairs, Thatcher cultivated a close political and personal relationship with US president Ronald Reagan, based on a common mistrust of communism, combined with free-market economic ideology. Critics have accused Margaret Thatcher of lacking a unified set of policies for much of her rule, but a set of practices and ideals have become identified with both her and her government: these are known as Thatcherism. The Thatcher government set about privatising most of the industries run by the government, including water, electricity and the trains, selling them off relatively cheaply to new private companies. She also clamped down heavily on trade unions, passing laws designed to curb strikes, closed shops and sympathy strikes.

One of the pivotal events of her government occurred in 1984: the Miners Strike. Britain’s miners protested the government closure of “uneconomic” pits. Thatcher organised Britain around the striking miners and forced them back into work with no concessions. Other aspects of Thatcherism included selling council houses to tenants, reducing social service expenses, limits on print money and a dislike of growing European federalism. She also lowered taxes. A fierce, combative approach, a strong individualism and other aspects of her personal style became closely identified with her politics. In the 1987 general election, Thatcher won an unprecedented third term in office. But controversial policies, including the poll tax and her opposition to any closer integration with Europe, produced divisions within the Conservative Party which led to a leadership challenge. In November 1990, she agreed to resign and was succeeded as party leader and prime minister by John Major.

Not long after leaving office, Thatcher was appointed to the House of Lords, as Baroness Thatcher of Kesteven in 1992. She experienced her experiences as a world leader and a pioneering woman in the field of politics in two books, The Downing Street Years (1993) and The Path to Power (1995). In 2002, Thatcher’s book, Statecraft, was published and offered her views on international politics. Around this time, Thatcher had a series of small strokes. She suffered a great personal loss in 2003 when her husband Denis died—the couple had been married for more than 50 years. In 2005, Thatcher celebrated her eightieth birthday. A huge event was held in her honor and was attended by Queen Elizabeth, Tony Blair, and nearly 600 other friends, family members, and former colleagues. Two years later, a sculpture of the strong conservative leader was unveiled in the House of Commons. While her policies and actions are still debated by detractors and supporters alike, Thatcher has left an indelible impression on Britain and world politics.

Upon Margaret Thatcher’s passing in 2013, Meryl Streep released a statement on the Former Prime Minister: “Margaret Thatcher was a pioneer, willingly or unwillingly, for the role of women in politics. It is hard to imagine a part of our current history that has not been affected by measures she put forward in the UK at the end of the 20th century. Her hard-nosed fiscal measures took a toll on the poor and her hands-off approach to financial regulation led to great wealth for others. There is an argument that her steadfast, almost emotional loyalty to the pound sterling has helped the UK weather the storms of European monetary uncertainty. But to me she was a figure of awe for her personal strength and grit. To have come up, legitimately, through the ranks of the British political system, class bound and gender phobic as it was, in the time that she did and the way that she did, was a formidable achievement. To have won it, not because she inherited position as the daughter of a great man, or the widow of an important man, but by dint of her own striving.

To have withstood the special hatred and ridicule, unprecedented in my opinion, leveled in our time at a public figure who was not a mass murderer; and to have managed to keep her convictions attached to fervent ideals and ideas – wrongheaded or misguided as we might see them now – without corruption – I see that as evidence of some kind of greatness, worthy for the argument of history to settle. To have given women and girls around the world reason to supplant fantasies of being princesses with a different dream: the real-life option of leading their nation; this was groundbreaking and admirable. I was honored to try to imagine her late life journey, after power; but I have only a glancing understanding of what her many struggles were, and how she managed to sail through to the other side. I wish to convey my respectful condolences to her family and many friends.”

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Margaret Thatcher (April 2013)

Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World by Margaret Thatcher (2002)

Messages from Croatia by Margaret Thatcher (1998)

The Collected Speeches of Margaret Thatcher by Margaret Thatcher (1998)

The Path to Power by Margaret Thatcher (1995)

The Downing Street Years by Margaret Thatcher (1993)

The Revival of Britain by Margaret Thatcher and Alistair Cooke (1989)

Britain and Europe by Margaret Thatcher (1988)

In Defence of Freedom: Speeches on Britain’s Relations With the World by Margaret Thatcher (1987)

Margaret Thatcher in Her Own Words by Macdonald Daly and Alexander George (1987)

Let Our Children Grow Tall: Selected Speeches, 1975-77 by Margaret Thatcher (1977)

“We are here, not because we are law-breakers; we are here in our efforts to become law-makers.” Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928) founded the Women’s Social and Political Union, which used militant tactics to agitate for women’s suffrage. Pankhurst was imprisoned many times, but supported the war effort after World War I broke out. Parliament granted British women limited suffrage in 1918. Pankhurst died before women were given full voting rights.

Emmeline Goulden was born in Manchester, England, in 1858. The eldest of 10 children, she grew up in a politically active family. Her parents were both abolitionists and supporters of female suffrage; Goulden was 14 when her mother took her to her first women’s suffrage meeting. However, Goulden chafed at the fact that her parents prioritized their sons’ education and advancement over hers. After studying in Paris, Goulden returned to Manchester, where she met Dr. Richard Pankhurst in 1878. Richard was a lawyer who supported a number of radical causes, including women’s suffrage. Though he was 24 years older than Goulden, the two married in December 1879, and Goulden became Emmeline Pankhurst. Over the next decade, Pankhurst gave birth to five children: daughters Christabel, Sylvia and Adela, and sons Frank (who died in childhood) and Harry. Despite her children and other household responsibilities, Pankhurst remained involved in politics, campaigning for her husband during his unsuccessful runs for Parliament and hosting political gatherings at their home. In 1889, Pankhurst became an early supporter of the Women’s Franchise League, which wanted to enfranchise all women, married and unmarried alike (at the time, some groups only sought the vote for single women and widows). Her husband encouraged Pankhurst in these endeavors until his death in 1898.

Coping with straitened circumstances and grief consumed much of Pankhurst’s attention for the next several years. However, she retained a passion for women’s rights, and in 1903 she decided to create a new women-only group focused solely on voting rights, the Women’s Social and Political Union. The WSPU’s slogan was “Deeds Not Words.” In 1905, Pankhurst’s daughter Christabel and fellow WSPU member Annie Kenney went to a meeting to demand if the Liberal party would support women’s suffrage. After a confrontation with the police, both women were arrested. The attention and interest that followed this arrest encouraged Pankhurst to have the WSPU follow a more combative path than other suffrage groups. At first the WSPU’s “militancy” consisted of buttonholing politicians and holding rallies. Still, following these tactics led to members of Pankhurst’s group being arrested and imprisoned (Pankhurst herself was first sent behind bars in 1908). The Daily Mail soon dubbed Pankhurst’s group “suffragettes,” as opposed to the “suffragists,” who also wanted women to be able to vote in the United Kingdom, but who followed less confrontational channels. Over the next few years, Pankhurst would encourage WSPU members to rein in their demonstrations when it seemed possible that a bill on women’s suffrage might move forward. But when the group was disappointed—as in 1910 and 1911, when Conciliation Bills that included women’s suffrage failed to advance—protests would escalate. By 1913, militant actions by WSPU members included window-breaking, vandalizing public art and arson.

Throughout these protests, suffragettes were arrested, but in 1909 the women had begun to engage in hunger strikes while in prison. Though this resulted in violent force-feedings, the hunger strikes also led to early release for many suffragettes. When Pankhurst was given a nine-month sentence in 1912 for throwing a rock at the prime minister’s residence, she too embarked on a hunger strike. Spared from being forcibly fed, she was soon freed. Seeking to circumvent the hunger strikes, in 1913 the Prisoners’ Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act was enacted. The law said that prisoners who were released for health reasons could be rearrested and taken back to prison once they’d recovered. It became known as the “Cat and Mouse Act,” with suffragette “mice” being pursued by the authorities. In 1913, after an incendiary device went off in an unoccupied house being built for the chancellor of the exchequer, David Lloyd-George, Pankhurst received a sentence of three years of penal servitude for inciting the crime. She was released after a hunger strike, but the Cat and Mouse Act led to a series of rearrests and releases—during one furlough, Pankhurst proceeded to the United States for a fundraising and lecture tour—that continued into 1914. But everything changed with the arrival of World War I. Feeling that suffragettes needed to make sure they had a country to vote in, Pankhurst decided to call for a halt to militancy and demonstrations. The government released all WSPU prisoners, and Pankhurst encouraged women to join the war effort and fill factory jobs so that men could fight on the front.

The contributions of women during wartime helped convince the British government to grant them limited voting rights—for those who met a property requirement and were 30 years of age (the voting age for men was 21)—with the Representation of the People Act of 1918. Later that year, another bill gave women the right to be elected to Parliament. Though all her daughters had been members of the WSPU at some point, Pankhurst was only able to celebrate the achievement of (limited) suffrage with Christabel, her favorite. As a pacifist, Sylvia had disagreed with Pankhurst’s attitude toward the war, while Adela had moved to Australia. Pankhurst still desired universal women’s suffrage, but her politics changed focus after the war. She worried about the rise of Bolshevism and eventually became a member of the Conservative party. Pankhurst even ran for a seat in Parliament as a Conservative, but her campaign was disrupted by ill health (exacerbated by the public revelation that Sylvia had given birth to an illegitimate child). Pankhurst was 69 when she died in London on June 14, 1928.

Pankhurst did not live to see it, but on July 2, 1928, Parliament gave women voting rights on a par with men’s.

Florence Foster Jenkins was a New York heiress and young piano prodigy, but her musical talent didn’t translate to her terrible singing voice. She obsessively pursued her singing dream with the help of her partner and manager St Clair. The English actor was desperate to protect her from the truth, which proved impossible when she decided to perform at Carnegie Hall. Jenkins was convinced the mockery and ridicule she suffered throughout her life was the product of jealousy.

In her time, Florence Foster Jenkins was a unique novelty in the history of music, an operatic coloratura who had all of the requisite charms and trappings worthy of a diva, minus the voice. Married to a wealthy industrialist and well entrenched in upper-crust New York society by 1912, “Madame” Jenkins obtained a divorce that year. The resulting settlement was handsome enough to set Jenkins up in style and to pursue her extensive charitable interests. She had already been studying voice for some time, and her charity fundraisers included such gala events as “The Ball of the Silver Skylarks,” involving special costumes made at her request, and usually culminating in a sample of her singing. Jenkins’ voice was high, scrawny, and seemed to have a mind of its own, warbling its way through difficult coloratura arias with the grace and control of an upright piano plunging down through a spiral staircase. Well-heeled society types would attend Jenkins’ recitals and patiently endure her auditory assault, along with enjoying a well-concealed chuckle or two at her expense. Jenkins’ annual gala would remain a popular fixture in New York society for decades.

In 1938, Jenkins made her only recordings at the Melotone studio in New York, which were pressed up and sold privately. On this occasion, and most others by this time, Jenkins employed the services of accompanist Cosme McMoon, a flamboyant and eccentric character well known in New York’s underground gay community. McMoon proved an excellent foil for Jenkins, waiting for her entrances at key points in arias and writing special material to best show off her vocal “assets.” At age 76, Jenkins finally achieved her lifelong dream of performing at Carnegie Hall’s Recital Hall on October 25, 1944, but this may have backfired, as rumor has it that afterward she discovered what her audiences really thought about her music-making. Jenkins collapsed and died a month later in Schirmer’s Music Store, her last words allegedly being “It must’ve been the creamed chicken.”

Rumors about Jenkins’ highly eccentric behavior are legion, and it is hard to know now which ones are true. The only way one could obtain a ticket to her high-priced galas was to buy one from Jenkins in person. Jenkins is said to have ordered flowers to be delivered to her concerts, and genuinely forgot that she’d done so, thinking the celebratory bouquet was from her admirers. She also once paid, according to legend, a handsome gift to a New York taxicab driver, as after she was knocked down by him in the street she could “sing a higher F than ever before.” Although known only to her immediate social circle during her lifetime, the legend of Florence Foster Jenkins has grown since her passing.

In Steven Spielberg’s ‘The Post,’ Meryl Streep brings Katharine Graham’s 1971 decision to have the Washington Post publish the top secret Pentagon Papers to life. However, even with the support of Tom Hanks as editor Ben Bradlee, there’s only so much that one film can include. Here’s the real story behind The Post.

Her success as one of the first women to be a major business leader in the US was all the more remarkable because it was thrust on her in early middle age by a tragic accident. She had reached the age of 46 as a wealthy but diffident housewife, the mother of four children, and the wife of the Washington Post publisher Phil Graham. Then her husband, a close friend of John F Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, and generally credited with persuading the former to take the latter as his vice-presidential candidate – a decision which many pundits believe made each of them successively president – suddenly blew up. Graham’s husband had been suffering from undiagnosed manic depression for some time. Then he started an affair with a young woman reporter from Newsweek and took her on a Lolita-like tour round the US, ending up at the 1963 convention of the Associated Press, where he grabbed the microphone, made obscene comments and started taking his clothes off. After an appalling succession of escapades and repentances, he returned home, and shot himself. His wife found the body. Warned by all her worldly-wise friends to leave the business, owned by her father before it passed to her husband, to be run by others, Graham decided that she owed it to her children to take over. She did this to such effect that she steered the paper through its transformation into a public company in 1971 and through violent strikes against new technology.

She was the publisher during the paper’s successful legal battle, in alliance with the New York Times, against the Nixon administration’s attempt to prevent them publishing the secret government documents on the origins of the Vietnam war known as “the Pentagon papers”. And she was still at the head of the Post at the time of its triumphant exposure of the various scandals collectively known as Watergate, which forced President Nixon’s resignation and transformed American journalism for ever. Kay Graham, as she was called, was born at the very centre of the expanding imperial America of the ragtime era. Her father, Eugene Meyer, was descended from an eminent family of rabbis and merchants in Alsace; his father was a partner in Lazard Freres, the investment bank. After studying at Berkeley and Yale, Eugene Meyer, too, joined Lazards, but soon founded his own investment company and within a short time was worth several million dollars. He met his future wife Agnes Ernst, the daughter of a German Lutheran family, in an art gallery when she was a student at Barnard College. Agnes Meyer had already formed friendships with several famous people, including the philosopher John Dewey, the photographer Edward Steichen and the painter Georgia O’Keeffe. She had spent a good deal of time in Paris, where she knew the sculptors Brancusi and Rodin and the salon of Gertrude Stein, of whom she did not think much.

All her life Agnes Meyer was a strong-minded, opinionated woman. Kay, her fourth child, not only got on badly with her in a dutiful sort of way, but reacted against her overwhelming style, which was more than a little reminiscent of Margaret Dumont in the Marx brothers’ films. One peculiarity of the family was that the children grew up not only not quite sure whether their father was Jewish, but obliged to ask what being Jewish meant. Partly as a result, Graham identified more closely with her Jewish (though secular) father rather than with her Protestant mother. During the first world war, Eugene Meyer founded the Allied Chemical Company to replace the German aniline dyes that were unobtainable by the American textile industry because of the war. It was said during the Watergate crisis that if Katharine Graham lost control of the Washington Post Company she would be down to her last $600m. Eugene Meyer went down to Washington to serve as the chairman of the War Finance Corporation, so even though the family kept its mansion at Mount Kisco, New York, it was in Washington that Kay Graham grew up, in a world that was just moving from the sedate atmosphere of Henry Adams’s 1880 novel Democracy to that of Gore Vidal’s Washington DC. One of Graham’s best friends at school was President Grant’s granddaughter. After attending Madeira in Virginia, the smartest private school for young ladies, Kay went on to Vassar. She would have liked to go to the London School of Economics, but her father put his foot down and she went to the University of Chicago instead, where she resisted attempts by the young radicals and communists to recruit her, protesting her faith in the capitalist system that had treated her father so well. In 1940 she married Phil Graham, a young man who had made it into the emerging American power elite from the unlikely background of a family who moved from poverty in South Dakota to seek a modest fortune in Florida. He went to a public high school in Miami, then an out-of-the-way southern town, and from there by way of the University of Florida, in even-more-backward Tallahassee, to the Harvard law school and a job, reserved for the most brilliant students, as a clerk to Justice Felix Frankfurter, then at the height of his influence on President Roosevelt and on the American ruling class in general.

By the late 1950s Graham’s husband had succeeded his father-in-law as publisher of the Post and emerged as what would now be called a significant power-broker in Washington. It would seem that his illness, whatever its deeper causes, was aggravated by his feeling that he owed everything to having married his boss’s daughter. The young, brilliant publisher of what became the most powerful newspaper in the capital – after he bought the Times-Herald in 1954 – and his attractive if shy wife were naturally in great demand. With the Kennedy inauguration in 1961, their generation and their friends took over both socially and politically. So when Katharine took responsibility for the family business, just before Kennedy’s assassination, she might be, as she always thought of herself, a mere housewife, inexperienced in the ways of business; but she was also on friendly and in many cases tennis and family-supper terms with most of the inner circle in Washington, and a card-carrying member of that well-born, well-heeled circle that came to be known as “the Georgetown set”. Eugene and Agnes Meyer lived in splendour in the Meridian Park section of Washington, where the pre-war grandees had their homes; the Grahams moved to the simpler elegance of Georgetown, where their mansion more than equalled the Georgian-style homes of the John F Kennedys, the Averell Harrimans, the Joseph Alsops and the other swells. Graham, alone, might find herself the only woman at business meetings, addressed as “lady and gentlemen”. But she had no shortage of contacts and advice from the Robert McNamaras, the McGeorge Bundys and the “great whales” of Congress, while in New York she began to run with the Truman Capote set, graced by such ladies as Pamela Harriman, Babe Paley (wife of the owner of CBS) and Marella Agnelli, whose husband owned Fiat. Her personal friends included the pianist Rudolf Serkin; Adlai Stevenson, whom she did not find as attractive as many other liberal ladies did; Jean Monnet, to whose virility, as she put it rather oddly in her excellent memoirs, she could personally attest; and later Warren Buffett, the immensely successful investor from Omaha who built up a large position in the Washington Post Company’s stock and became Graham’s most trusted business mentor.

In lifestyle and manner, Graham was both genuinely diffident and unmistakably a magnifica, if that is the word for a female magnifico . She could be, as it seemed alternately, charmingly direct and friendly, and aloof, even arrogant. Interviewed in what seemed to her an insufficiently respectful way by the British journalist Henry Fairlie, she reproved him by saying she had been told by no less an authority than McGeorge Bundy that she was the most powerful woman since Queen Victoria. On another occasion, when a newly arrived British ambassador expected her to join the ladies after dinner, she summoned her car and swept imperiously from the embassy. No doubt the truth was that she was lonely and often overwhelmed by the perils threatening her dynasty and her beloved newspaper – perils that she by no means underestimated. She was at first unsympathetic to the tide of feminism which was rising to storm levels in the 1970s, and nowhere more than in the newsrooms of papers and magazines, where talented women found themselves not only professionally discriminated against, but also treated with sometimes brutal insensitivity. The feminist journalist Gloria Steinem, the founder of MS magazine, tried, with little success at first, to interest Graham in the movement. A stronger influence was that of Meg Greenfield, an editorial writer and later editorial page editor of the Post and a columnist for Newsweek, who became Graham’s closest woman friend.

“Though it took me a long time to throw off my early and ingrained assumptions,” she wrote in 1997, in her notably frank and highly successful autobiography, “I did come to understand the importance of the basic problems of equality in the workplace, upward mobility, salary equity and more recently child care.” Although she lived most of her life in an intensely political environment, was generally perceived, especially by conservatives, as a liberal, and indeed proclaimed herself to be a typical “limousine liberal”, her political attitudes and loyalties were more complicated than they seemed to many. Her father, and especially her mother, started out as Republicans, and her husband, before becoming a major Democratic power behind the scenes, voted for the Republican Eisenhower in 1952. At first she made overtures to President Nixon. Then, when her paper was threatened by his administration in the Pentagon papers case and again when the Washington Post Company was in danger of losing its TV franchises during the Watergate battle, she was fiercely antagonistic to the Nixon administration. This was hardly surprising, since Nixon’s vice-president, Spiro Agnew, singled the paper out among the “effete eastern snobs” who dominated the media. And when the young Post reporter Carl Bernstein called Nixon’s attorney general, John Mitchell, to check his involvement in the Watergate affair, Mitchell said: “Katie Graham’s going to get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published.” During the Watergate crisis, Graham forged a close relationship with Ben Bradlee, the tough, salty-spoken editor she had brought across from Newsweek. Although not directly involved – as she had been in the Pentagon Papers fight, when she personally took the crucial decision to publish the documents – she identified totally with the Post’s investigative reporting. Later, however, she surprised many and disappointed some by forming close friendships with Henry Kissinger and his wife Nancy, and later with Ronald and Nancy Reagan. It would seem that, like many “neo-conservatives” who moved to the right as a result of the wild confrontational politics of the 1970s, Graham’s New Deal loyalties were shaken by her confrontation with the unions, in which the pressmen, in particular, used violent tactics and threatened even uglier attacks.

Certainly, one of her strongest motivations was her commitment to her family and to the media and business empire her father and then her husband had built. It was a great pleasure for her that her daughter, Elizabeth “Lally” Weymouth, worked at the paper before building a career as a freelance journalist, and an even greater satisfaction to be able to hand over the post of chief executive officer of the Washington Post Company in 1991 to her son Don, who had come to the paper only after serving in Vietnam and then working as a District of Columbia police officer. In 1977, she was a member of the Brandt Commission on north-south relations. She was immensely pleased when one of the Third World radicals on the commission made a pass at her. She said her motto was “Never where you work,” and her admirer replied that his was “Never say never.” After her retirement, she travelled widely and sent back interviews with the likes of Mikhail Gorbachev, the Shah of Iran and Muammar Gadafy. She was proud of the fact that Newsweek printed a photo she took of Gadafy, and framed the cheque for the $87.50 she was paid.

In later years Graham spent much time on Martha’s Vineyard, which she loved. She is survived by her daughter Lally and her three sons, Donald, Steve, a New York theatrical producer, and Bill, a lawyer.

The year 2020 was affected by the novel COVID19 virus and its worldwide pademic. The adaptation of the hit muscial „The Prom“, directed by Ryan Murphy“ was halted during production in the spring of 2020 and finished during mid-year. Meryl’s other production, Steven Soderbergh’s experimental „Let Them All Talk“, was finished already before the start of the pandemic. Both films were released in December of 2020 on demand – „The Prom“ on Netflix, „Let Them All Talk“ on HBO Max. With all public appearances stopped, Meryl Streep participated in numerous online appearances to honor causes and raise awareness on special programmes.

Meryl Streep joined Reese Witherspoon, Nicole Kidman, Shailene Woodley and Laura Dern for HBO’s second season of the outrageously successful “Big Little Lies”. While the second season was not as much-loved as its predecessor (mostly for the fact that the initial storyline was completely finished), the show still entertained with Streep’s addition, playing the suspicious mother to Alexander Skarsgård’s wife-beating character, who comes to Monterey demanding answers to what really happened to her son. The performance brought Streep another Golden Globe, Screen Actors Guild and Emmy nominations. In October 2019, she made a proper Netflix debut starring in Steven Soderbergh’s wildly odd “The Laundromat” as a widow trying to unlock the myriads of backdoors in the finance industry that keep her from getting the insurance money she and her husband have paid all those years. On Christmas, she was seen on the big screen as Aunt March in Greta Gerwig’s “Little Women”, which received an Academy Award nomintion for Best Picture.